Kashmir Is An Experimental Lab

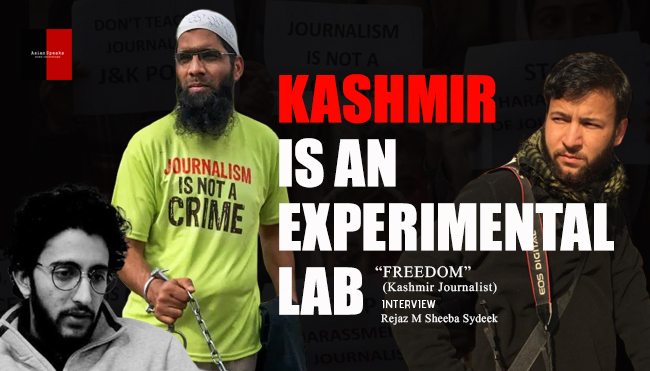

On May 2 2023, Rejaz M Sheeba Sydeek interviewed a well-known journalist in Kashmir who has been under the radar of state violence in the valley. The journalist has requested anonymity, anticipating repercussions from the Indian government. To maintain the anonymity the interviewee is named “Freedom“.

The political reason behind this small and quick interview can be understood from the request for anonymity. Here anonymity cannot be seen through the prism of cowardice but reflects the very reality of “Democracy and Independence” in the largest “Democratic country of world”, India and the present state of press freedom in Kashmir and mainland India. India climbed down to the 161st position out of 180 countries in the 2023 World Press Freedom Index released by Reporters Without Borders on May 3, 2023.

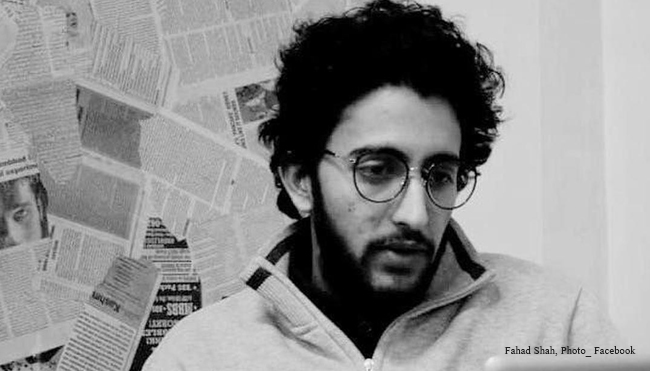

Incarceration of Kashmiri journalists, Aasif Sultan, Fahad Shah, Sajad Gul and Irfan Mehraj are few examples of how Press Freedom is dying a slow death in Kashmir and India.

To speak about the same I contacted at least 10 Kashmiri journalists, but most of them were not ready to speak on record and politely declined citing repercussion from the state and state violence.

Another award winning Kashmiri Muslim journalist who was also jailed gave the interview, but technical issues and loss of contact with them demanded a new interviewee.

This interview was done within the tight schedule of interview and multiple limitations. This is the transcribed interview which was conducted by Rejaz and a few changes have been done in order to make it more clear and understandable.

_ Rejaz M Sydeek

Rejaz: India is going through an undeclared emergency period and the fourth pillar of democracy is being sabotaged by the remaining three pillars. Kashmir Press Club was shutdown by government and India was ranked 150 out of 180 countries by “Reporters without Borders” in their 2022 World Press Index. For how long has Kashmir Press been undergoing an emergency phase while being jailed within a large prison that incarcerates nationality? Do you think that there is a need to give exclusive attention to address the present situation of press freedom in Kashmir?

Freedom: Regrettably, the deteriorating state of press freedom in Kashmir frequently fails to attract significant attention or coverage. It appears that Kashmiri journalists persistently endure these challenges without garnering the serious concerns, support, or follow-ups that they deserve. The daily oppression inflicted upon them by state authorities continues largely unnoticed. It is perplexing and beyond comprehension why the plight of Kashmiri journalists receives such limited backing. Their experiences surpass the hardships faced by journalists in mainland India, creating a stark contrast. The lack of support for Kashmiri journalists leaves me puzzled, as there could be multiple reasons contributing to this disheartening reality.

The shutdown of the Kashmir Press Club needs to be viewed within the broader context of a widespread crackdown on the media. Personally, I did not consider the closure of the press club as a sudden turning point. It was a gradual erosion of our rights as journalists that we witnessed day and night until the eventual shutdown. While it was not entirely surprising, it did represent a significant setback for us.

Kashmir’s journalists’ community has been facing these crackdowns for a very long time. But post August 2019, there was a sense of urgency was seen among the state authorities that the press clubs needed to be cracked down, so it worsened.

Rejaz: Stories against state violence, corporate loot, military harassment, poverty and human rights violations disturbs the government. Can we say that Journalism is for the freedom of people from oppression? How are Kashmiri journalists helping the common people in the conflict zone?

Freedom: I wouldn’t go as far as stating that journalism solely exists for the purpose of liberating people from oppression. In Kashmir, journalism has predominantly focused on journalism itself for a considerable period. Rarely was there an ulterior motive to achieve a specific outcome. Many times, our primary objective was simply to ensure that a story was published, allowing people to react and interpret it according to their own understanding and also to let people know outside Kashmir that what is happening here.

Things are not black and white here, they are very much grey. A lot of times, when these stories come out, they are able to put light on many human rights violations that keeps happening in the valley. Mostly, these stories are either sidelined by mainstream media or simply ignored but sometimes these stories are able to spark public discussions around the issue and louder the public conversation I think effective the story is and the same public attention works as a shield for the people whenever there is a state action against these subjects of the stories.

Add to this, I have also seen people as in subjects suffering the state repercussions after a reporter cover any story and move on with it, I would say that some Journalists only look at Kashmiris as mere stories, subjects and fuel for their careers.

Rejaz: The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh killed journalists like Gauri Lankesh, who spoke against Brahmanic Hindutva fascism, and is suppressing the voices of journalists like Rupesh Kumar Singh and Gautam Navalakha who are languishing in jail under stringent UAPA for doing critical journalism and speaking for Kashmir, minorities and against imperialism. How do you analyse journalism and view media freedom outside Kashmir?

Freedom: There is a very popular saying that many of these crackdown practices are first experimented in Kashmir and Kashmir is an experiment lab. When it works out in Kashmir, it is extended to the rest of India. They say, “We tried this to suppress the media or people here, and that worked. Let us play it out in the rest of India as well”. I have seen that happening often, not just with journalism but with many other policies of this government as well.

On journalism outside India, I won’t say that it has gone from bad to worse because that is like saying there are 24 hours a day or some lame examples like that. Everybody knows what happened to journalism in India. There is due credit to many journalists who are still trying to do objective journalism from whatever means and resources they can and by them Journalism is surviving in India to some extent. But yes, it has gone down to docks, in short.

Rejaz: Kashmiri journalists, especially Kashmiri Muslim journalists, are often accused of glorifying “terrorists” similarly lawyers appearing for UAPA prisoners are seen as “friends of terrorists”. How do you professionally see it, especially when Islamophobia and xenophobia against Kashmiris are prevalent?

Freedom: I think this question is an important one. Because it partly answers the initial idea what I was initially saying that there isn’t a lot of support for Kashmiri journalists from mainland India. I believe that it is due to the identity of journalists as Kashmiri Muslims. It is very easy to label a Muslim in this country as a terrorist or a terrorist sympathiser. So, when it is a Kashmiri Muslim and that Kashmiri Muslim is a journalist writing about state oppression, it becomes like a cakewalk for the state that they can say anything and get away with it. I have seen that; we all have seen that happening.

Rejaz: What do you think are the reasons for most Indian journalists and media bodies being silent on the arrest of Fahad Shah, Irfan Mehraj, Sajad Gul, and Aasif Sultan?

Freedom: There is a bias when it comes to writing and taking a tand for a Kashmiri Muslim journalist, and regarding the reason, I think identity plays a significant role in that.

Rejaz: Draconian laws like UAPA, PSA, and Sedition are slapped on journalists, giving the message that journalism is a crime. Many Kashmiri journalists are reported to have left this profession because of state repression. How can impunity for crimes against journalists be ended?

Freedom: I think it is based on the policy decisions and that the government needs to realise that democracy can only flourish when reporters are allowed to report. That is when they would be able to see the merit of their policies and what the impacts of their policies on the ground are. Only then will they be able to make it better, but it would be a foolish statement or a utopian idea that I would be thinking if that is going to happen because this or the previous government are no champions of democracy. They anyway don’t want to make things better, transparent and easy for people; they are not willing to look at the brighter side of what will happen if press freedom will be improved.

Therefore, the notion of them attempting to rectify their policies seems highly far-fetched idea. We have witnessed the establishment of alarming precedents, and without a widespread, unified support or opposition resistance against these precedents, meaningful change becomes remote and unimaginable.

Let’s say when Gautam Navalakha was arrested, if there would have been a very widespread united resistance opposition to it, it could have make the government bow down and accountable. Until and unless that happens, if there is this popular support, then there will be more and more dangerous precedence that will continue to set, including Fahad, the Kashmirwalla’s editor arrest. Fahad’sarrest came to me as a watershed moment for journalism in Kashmir. Because, post that, there is radio silence, with literally no story coming out. Just try to open the pages of any newspaper from Kashmir. Let’s say, Greater Kashmir, Rising Kashmir, and Kashmir Observer – and see how their Page 1 looks like.

They all are full of advertisements funded by Lt. Governor (LG), leads are of LG, andsecond lead stories are of LG. The publications in Kashmir has just transformed only as the messenger of the Government’s Department of Information. It’s just the handouts. They have been reduced to the printing press of the government. This has been deliberately inculcated, pushed forward. The entire coverage of the newspapers is based around what LG has to say about this and that, what the police have to say and that’s all. That’s the entire news that is coming out of Kashmir right now.

Rejaz: I have read about family members of Bangladesh journalists being harassed and attacked by the government. What are the difficulties faced by the family members of Kashmiri journalists? How badly is the mental health of journalists affected?

Freedom: A well-known saying goes that when a young person is imprisoned, it is not only the individual who suffers, but the entire family held captive. These families endure the burden of repression and intimidation inflicted upon journalists by the government and state authorities. This situation often evokes a profound sense of guilt, as one’s family becomes entangled in the ordeal. While they are not criminally liable, the emotional toll is such that you begin to feel responsible for involving them in this struggle. It can be likened to a war we continuously face, but our families are involuntarily drawn into this conflict without any choice. They become hostages to the circumstances created by the government.

Rejaz: Your journalism is in the most militarized zone in the world. Have you personally or your news agency faced any surveillance or attack from the Indian state, especially during the era of digital surveillance?

Freedom: The sense of surveillance is always there. Every Kashmiri journalist working in Kashmir continues to look behind their shoulder to see who’s watching them, whether they are followed or their calls are heard. The eyes are always out of the windows.

In the sense of attacks on the press, I think that is all that’s happening. The attacks are continuous and repetitive. Sometimes, they are so ruthless that you want the final lockdown punch and want it all to be over, for once and all. But no. It’s a very slow and gradual death of journalism we are going through right now, and it’s an excruciatingly painful experience.

Rejaz: How did Covid and the revocation of Article 370 affect media in Kashmir?

Freedom: The Covid situation and revocation of Article 370, along with the lockdown during that time, greatly impacted revenue and the ability to move around. We have seen that the government using situations like Covid and lockdown post revocation of article 370 as tools to further suppress media freedom in Kashmir. The movement wasn’t allowed. We weren’t allowed to report even regarding the medical facilities in the region. The state invoked Disaster Act against people who were writing on Facebook and Twitter. No one was spared,everyone including journalists and citizens faced the wrath.

Rejaz: Finally, some argue that journalism is not political activism. Do you agree with this view, particularly in the context of Kashmir and the political nature of draconian laws used against journalists?

Freedom: Talking in the sense of a textbook answer, I would rather say that journalism is not political activism. But simultaneously, when we talk about Kashmir, it becomes political. Everything becomes political. What the mainstream press of Kashmir is writing and publishing today is a political idea. It’s like furthering a particular political idea. When we talk about Kashmir or the larger sense of India today, we can’t distinguish between the two. Journalists would instead not do it. But they often have the power and tools to create conversations that lead to political activism eventually. That is my primary idea of it.

Photos Courtesy_ Various Media